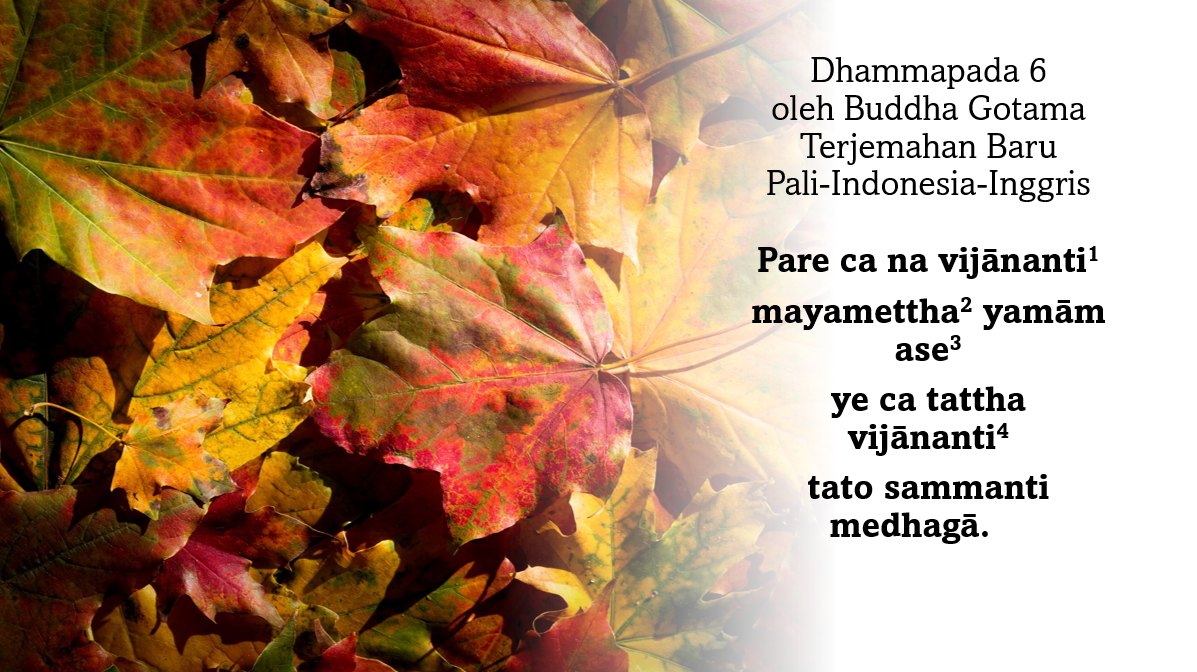

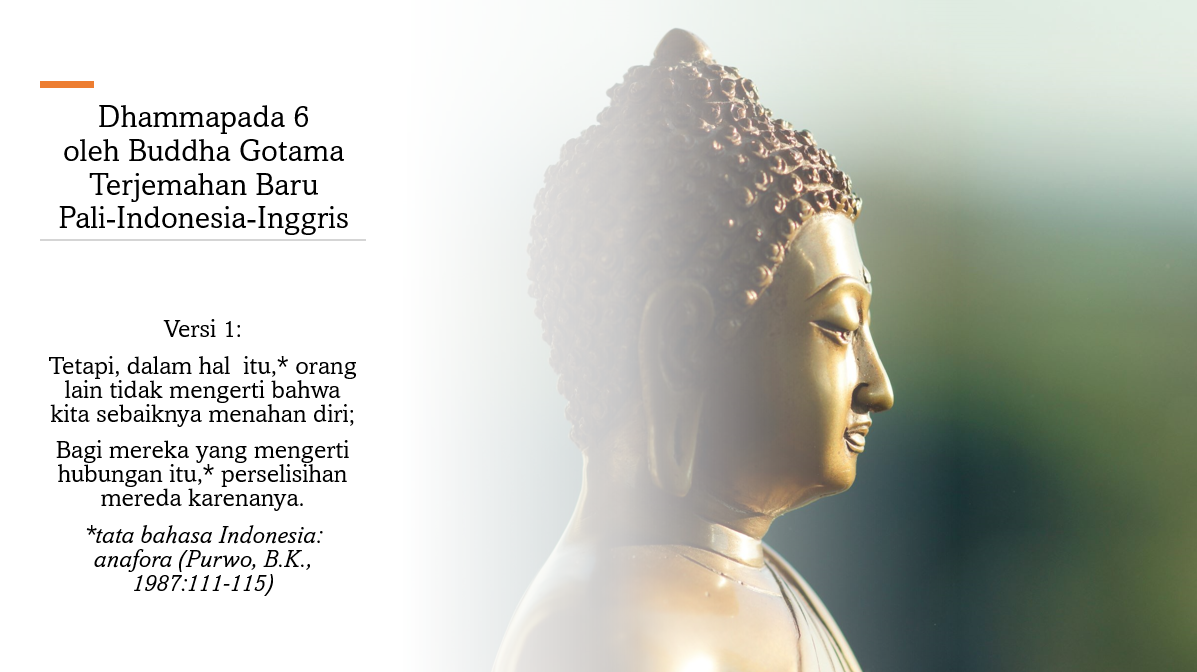

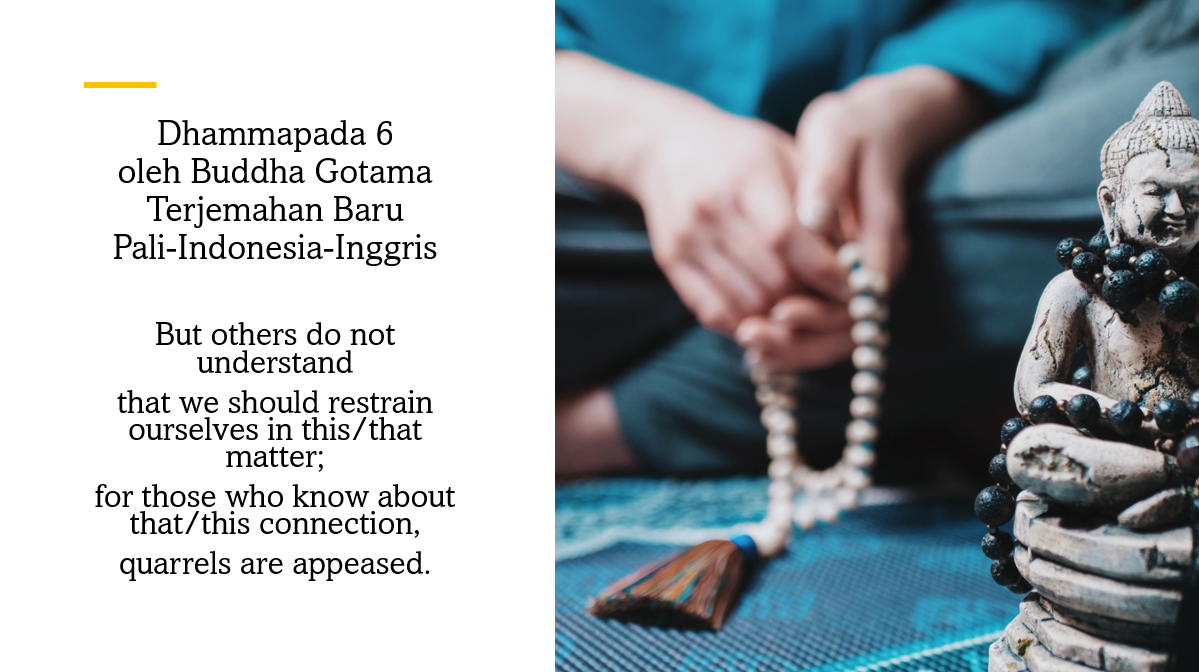

Yamaka Vagga

Vocabulary 1

|

Vocabulary 2

|

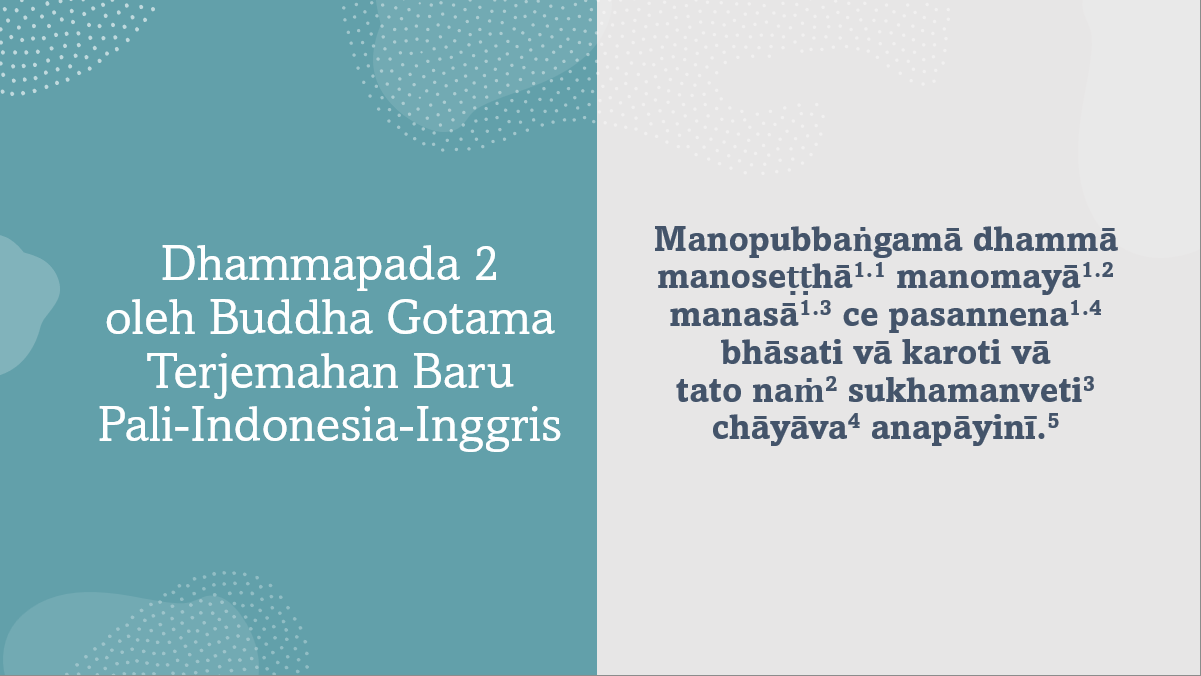

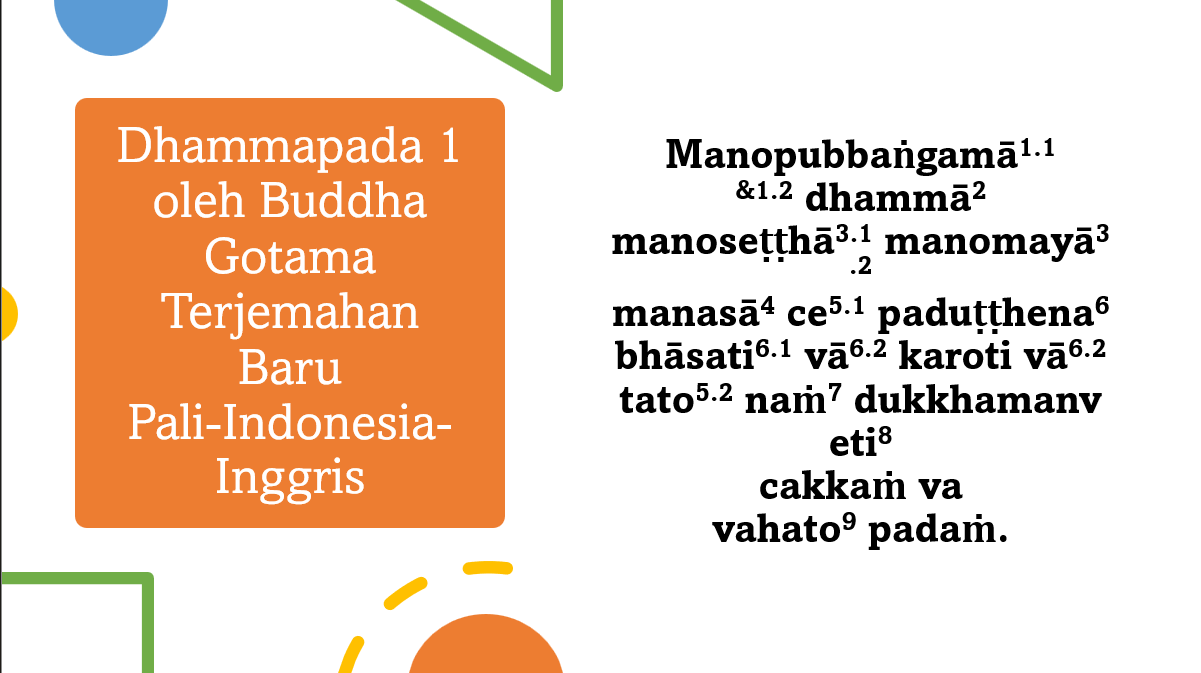

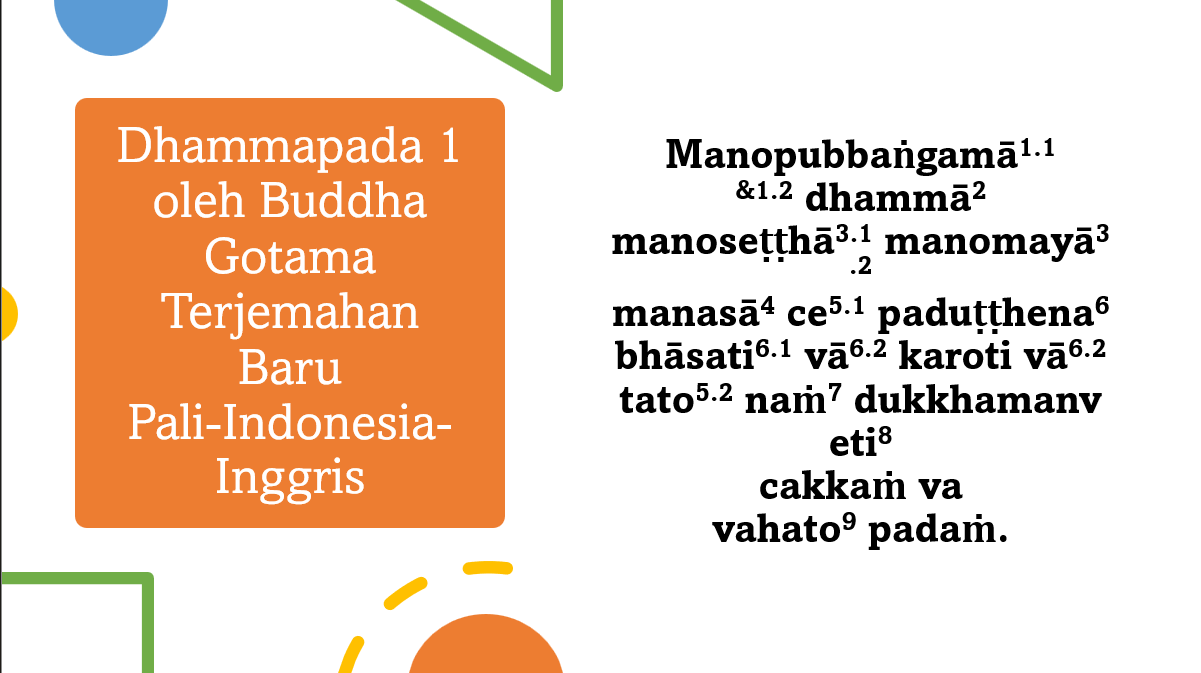

manopubbaṅgamā: (pl. masc. nom.) fig. directed or dominated by mind, having mind as the director or master; lit. having mind as what foreruns, precedes, leads, or goes before or in front

dhammā: (a) mental phenomena, the cetasikas; (b) masc. pl.nom. case of dhamma, mental phenomenon

manoseṭṭhā: (a) (pl. masc. nom.) (who, or what, are) led by mind, mind is their chief or best; (b) short form of manoseṭṭhā dhammā ‘mental phenomena (which are) led by mind, or mind is the chief of mental phenomena’

manomayā: (pl. masc. nom.) produced or created by mind

manasā: (sg. nt. ins.) by or with mind

ce (encl.) if

paduṭṭhena: (a) (sg. nt. ins.) evil, greatly corrupted; (b) derived from paduṭṭha ‘evil, greatly corrupted’ + -nā, a suffix meaning by or with, used to form the ins. case of a masc. noun and a neuter noun;

manasā paduṭṭhena: with an evil mind

|

bhāsati: (a) (she, he, or one) speaks; (b) also spelled as bhāsatī as the product of metri causa; (c) sg. 3rd pers. pres. act. indic. of the stem bhāsa, formed from the root √bhās ‘to speak,’ + a- + -ti, a suffix used to form a sg. 3rd. pers. pres. act. indic. tense

vā (encl.) = or; when repeated: vā… vā = either…or…

karoti: (a) (she, he, or one) acts, does, makes; (b) sg. 3rd pers. pres. act. indic. of the stem karo, formed from the root √kar ‘to act, to do, to make’ + -o + -ti

tato: (a) (sg. abl. and adv.) hence, then, from this, from that, thereupon, thereafter; (b) sg. abl. of pron. base ta ‘it, this, that,’ but used here as an adv.

naṁ: (a) him, that one; (b) sg. masc. acc. of the demonstr. pron. ta ‘he, this, that’

dukkhamanveti: (a) suffering follows; (b) a euphonic union, or sandhi, of (nt.) dukkha ‘suffering’ + –ṁ (a suffix indicating a sg. nt. nom. & acc. and sg. masc. acc.) + anveti ‘follows’

cakkaṁ: (a) (sg. nt. nom.) wheel; (b) derived from cakka ‘wheel’ + –ṁ, a suffix indicating sg. nt. nom. & nom. and sg. masc. acc.); cakkāni (pl. nt. nom.) ‘wheels’

va: (encl.) like

vahato: (sg. masc. gen.) of a bearer, an ox, of one who or which bears

padaṁ: (a) (sg. nt. acc.) foot; (b) a euphonic union, or sandhi, of pada ‘foot’ + –ṁ, a suffix indicating sg. nt. acc. & nom. and sg. masc. acc

|

Pali Grammar:

1.1mano: (i)(a) mano & mana(-s) (nt.) (see Note 4 below: manasā): like all other nouns of the old s-stems, mano has partly retained the s forms (cp. cetas > ceto) & partly follows the a-declension. The form mano is found throughout in compounds as manoo.* From stem manas, an adj. manasa and the der. mānasa & manasa is formed …. (Davids, 1921-1925/2005, Part VI, p.144); (b) However, Anuruddha (2004:745) mentions certain idiomatic expressions where mano stands as a single word: Yaṁ cittaṁ taṁ mano, yaṁ mano taṁ cittaṁ; other examples: Mano nābhiramissati ‘Mind does not (or will not) have any special interest;’ (ibid., p. 696): mano patisaraņņaṁ, mano ca nesaṁ gocaravisāyaṁ paccanubhoti ‘ mind is the support, and mind enjoys their realm;’ mano vuțțhahissati ‘(my) mind will rise up (from all forms of existence);’ (c) Perniola (1997:39, No.33) writes “There are a few stems in -s which are neuter in gender and are declined only in the singular. Such stems are: ayas ‘iron,’ uras ‘breast,’ cetas ‘mind,’ chandas ‘metre,’ jaras ‘old age,’ tamas ‘darkness,’ tapas ‘heat,’ tejas ‘splendour,’ manas ‘mind,’ yasas ‘fame,’ vacas ‘word,’ vayas ‘age,’ siras ‘head,’ etc.”

Nom., Voc., Acc mano

Inst., Ablt. manasā

Gen. manaso

Loc. manasi

- These stems are often declined like neuter stems in a-: manaṁ, manena, manasmā, manassa, manasmiṁ, manāni, manehi, manānaṁ, manesu.

- The comparative adjective in -yas: seyyas, pāpiyas, bhiyyas etc have nominative, vocative and accusative in -o: seyyo, papiyo, bhiyyo. In ther other cases, they are declined like the stems in -a. the adjective bhiyyo has an instrumental case bhyuyyena in the word yebhuyyena.

- There is a masculine in -as: candimas ‘moon’ which has chandimā in the nominative singular. For the rest, it is declined like puriso: candimaṁ, candimena, candimassa etc.

(ii) final -as and -ar become -o: tato ‘therefrom’ = Skt tatas; pāto ‘early in the morning’ = Skt prātar. Both the forms puno and puna ‘again’ = Skt punar are found to occur. In verbal inflection, there often appears -a for Skt -as (§§ 157, 158.II) …. [Geiger, 2005, §66, p.58(a)];

(iii) the intellectual aspect or part of viññana (or consciousness); nominative case; its stem is manas (adj.) (Davids, 1921-1925/2005, Part Vi, p.90); (iv) mind, a person’s intellect (Oxford Am. Engl. Dict.); (v) ‘What has the characteristic of cognizing should be understood, all taken together, as the consciousness aggregate’ was said above. And what has the characteristic of cognizing (vijᾱnana)? Consciousness (viññana); according as it is said, ‘It cognizes, friend, that is why “consciousness” is said (M.i.292). The words viññana (consciousness), citta (mind, consciousness), and mano (mind) are one in meaning (Vsud: XIV.84); (vi) … It measures (muņati), thus it is mind (mano). (ibid. XV.3); (vii) … due to eye and visible objects, eye consciousness arises, …. due to mind and mental objects, mind consciousness arises’ (M.i.III) (ibid.XIV.12); (viii) The 68 kinds of mind-consciousness element are the ‘mind-consciousness (or mano-viññana) element.” (ibid. XVII.120); (ix) mano, mind, in the Abhidhamma is used as synonym of viññana and citta (state of consciousness, mind) (Nyānatiloka & Nyānaponika, 1980:183); (x) In the traditional Buddhist list of the six senses and their respective objects (āyatana), mano refers to the sixth sense, cognitive consciousness (Fronsdal, 2011:96).

1.2 manopubbaṅgamā:

(i) (a) a tappurisa samāsa [Perniola, 1915/1997:165(c)], contraction of manas+ pubbaṅgamā, with manas changing its final -as to -o; in many cases, however, the stem has passed to the thematic stem: āpas-maya > āpomaya ‘made of water’ [Duroiselle, 1915/1997, p. 159(i)]; (b) Duroiselle (ibid.,p.15, No.45) also writes that a niggahīta may sometimes be inserted before a vowel or consonant: ava siro= avaṁsiro; manopubba+gama= manopubbaṅgamā; cakkhu+udapadi= cakkhuṁ udapadi; yāva c’idha= yavañc’idha;

(ii) (a) 3rd pers. plu. nominative case of manopubbaṅgama, meaning (a) preceded by mind, or (one who has) mind as the forerunner; (b) directed by mind, or dominated by mind (Davids, 1921-1925/2005, Part V, p.145),(b) ‘mind precedes’ (Gogerly,1840/1908:250;

(iii) manopubbaṅgamā, a pakatisandhi, or natural sandhi, or euphonic change compound (A. Bhikkhu, 2021:32, quoting Kaccāyana § 23);

(iv) pubbaṅ: (a) an adverb, derived from pubba ‘before;’ it either remains as pubba or changes (in order to produce a euphonic combination, or sandhi) into pubbaṅ before gama (Davids, 1921-1925/2005, Part V, p.90) (sg. masc. nom.) or gamā (pl. masc. nom.); (b) pubba is also an adjective meaning former, or previous, or ancient; pubba is never used in its absolute forms, but in compounds, and is put either before or after the word it is compounded with, e.g., pubbācariya ‘former, or previous, or ancient teacher,’ pubbakamma ‘previous or former action,’ pubbanimitta ‘previous sign, prognostic sign, portent,’unless in poetic phrases, e.g., pubbaṁ antaṁ for pubbantaṁ ‘the East’ (ibid.);

(v) gamā: pl. masc. & nt. nom. cases of (a) gama ‘going to,’ derived from √gam ‘to go’ + -a with the kita, or primary derivation, -a suffix changing the verb into an adjective; the same suffix also forms nouns, called as verbal nouns, from verbs, which is either the doer of the action or the action: gāma ‘goer’ or ‘going;’ √kar ‘to do, to make’ +-a= kāra ‘doer, maker, that which makes does or ‘doing, making’ (Duroiselle, 1915/1997:141, No. 576), (b) with the lengthening of the a in the roots gam and kar to ā (ibid, No. 567).

2 dhammā:

(i) Declensions of dhamma, a masculine noun (Tilbe, 1899:19-20, No. 127):

singular plural

Nom. dhammo dhammā

Gen. dhammassa dhammānaṁ

Dat. dhammassa, dhammāya dhammanaṁ

Acc. dhammaṁ dhamme

Ins. dhammena* dhammehi, dhammebhi**

Abl. dhammā dhammehi, dhammebhi**

dhammasmā

dhammamhā

dhammato

Loc. dhamme, dhammesu

dhammasmiṁ, dhammamhi

Voc. dhamma, dhammā dhammā

*dhammena: (a) euphonic combination or union, or sandhi,* of dhamma and the 3rd. pers. sg. masc. or neuter instrumentative suffix -ena ‘with, by’ with the elision or suppression sometimes of the final vowel in the first word (Tilbe, 1899:7, No.67), in this case dhamma, or of either the final vowel in the first word or the initial vowel of the second word, e.g., pana ime ‘but these’ > either paname or panime (Clough, 1824:9, No.18), or pana’me; tena+ime = tena’me (Duroiselle, 1915/1997:8, No. 21(b)); (b) when two different vowels come together, in this matter the final a in paduṭṭha and the initial e in -ena, usually the first, i.e., the final a, is elided and the second vowel, i.e., the initial e is lengthened if it happens to be in an open syllable: purisa ‘man’ + -ena > purisena ‘with a man;’ buddha-uppādo > buddhuppādo ‘the arising of a buddha;’ mano-indriyaṁ > manoindriyaṁ ‘the faculty of the mind.’

** (i) The forms in –bhi are mostly poetic (Tilbe, 1899: 10); (ii) The suffix –ebhi is mostly used in poetry and probably comes from the Vedic -ebhis [Duroiselle, 1915/1997:27(f), No.122], or archaic (Geiger, 1916/2005:73).

(ii) the nominative plural case in -ā of neuter stems is not rare in the first two periods, namely, Gāthā and canonical prose periods, of the language: rupā ‘figure’ Th 455; sotā ‘ears’ Sn 345; nettā ‘eyes’ Thī 257; phalā ‘fruits’ Ja IV 203. These forms were still felt to be neuter, e.g., tin’ assa lakkhanā gatte Sn 1019; moghā (cty: moghāni); te assupariphanditāni Ja III 24.25. They correspond to the Vedic pl. forms in -ā, e.g., yugā ‘yokes’ (Geiger, § 78, p.71.6); however, dhammāni, accusative case, is found in Stanza 82) (Tjan);

(iii) rarely treated as a neuter (Davids, 1921-1925/2005, Part IV, p.171), the pl. nom. case of dhamma is either dhammā or dhammāni* (Tilbe, ibid., p.21, No.129) = mental phenomena. For the two forms of the pl. nom. cases of rupa and other neuters ending in a, see Duroiselle (1915/1997:27, No.123 & 124): rupa > rupā & rupāni, citta > cittā & cittāni, with the final a in the stems rupa and citta being lengthened to a before the suffix -ni. The suffix ni- is essentially the distinctive sign of neuter nouns in the pl. nom., acc., and voc. cases in all declinations [ibid., No.124(a) & (b)]

*dhammani: only found in S1 103 where the Comny takes it as a locative and, gives, as the equivalent, “in a a forest on a dry land” (araññe thale) (Davids, 1921-1925/2005, Part III-IV, p.175);

(iv) a multi-significant term. Here it is used in the sense of thing, condition, or state (Narada & Pereira, 1940:1);

(v) refers to what is cognized, that is, anything within the sphere of empirical experience. Dhammā can also refer specifically to all mental states (Fronsdal, 2011:96);

(vi) plural form dhammā ‘mental faculties (vedanā, saññā & sańkhāra)’ (Müller & Fausböll, 1881, 2011:54);

(vii) perception…mental states: the pure event of seeing, hearing, etc. an object is ‘perception;’ the concurrent rise of attachment, hate, anger, desire, etc. with regard to it, is the mental states (Carter & Palihawadana, 2000:72).

***Manopubbaṅgamā dhamma in “tena pathama gamina hutva samaññagata” of Dh.A.1.35 (Davids, 1921-1925/2005, Part V, p.90)

****Narada & Pereira, 1940

(vii)manopubbaṅgamā dhammā:

(a) All mental phenomena have Mind as their forerunner in the sense that Mind is the most dominant, and it is the cause of the other three mental phenomena, namely, Feeling (vedanā), Perception (sañña) and Mental Formations or Mental Concomitants (saṅkharā). These three have Mind or consciousness (viññana) as their forerunner, because although they arise simultaneously with Mind, they cannot arise if Mind does not arise (Tin, 2003:1);

(b) Mind is the forerunner of (all evil) conditions (Narada & Pereira, 1940:1);

(c) Mind precedes all mental states (Buddharakhita);

(d) All states arising have mind for their causing (Woodward,1921-2003:1);

(e)Creatures from mind their character derive (Edmunds, 1902:1);

(f) Mental phenomena (are) preceded by mind (Sarao, 2009:1);

(g) All that we are is the result of what we have thought (Mūller & Fausböll,???)

(h) Manopubbaṅgamā dhamma in “tena pathama gamina hutva samaññagata” of Dh.A.1.35 (Davids, 1921-1925/2005, Part V, p.90);

3.1manoseṭṭhā: (i) mana(-s) (nt.) = mind;

seṭṭha (adj.) excellent, best; manas + seṭṭha= manoseṭṭha

(adj.) (one who has) mind as the best, i.e., mind as a master or leader;

manoseṭṭhā (pl. masc. nom.) = (those who have) mind as a

master or leader (Sarao, 2009:2); (ii) (a) a kammadhāraya samāsa [Perniola, 1915/1997:165(c)], contraction of manas+seṭṭhā, with manas changing its final -as to -o (see Note 4 below: manasā); in many cases, however, the stem has passed to the thematic stem: āpas-maya > āpomaya ‘made of water’ [ibid., p. 159(i)]

3.2 (i) the cetasikas, or mental concomitants (Narada & Pereira, 1940:1); (ii) manomayā:

manomaya (adj.) = (which is) produced by mind; manomayā (pl. masc. nom.) = (which are) produced by mind (Sarao, 2009:2); (iii) Contrast the cpd manomayā with cittakataṁ ‘decorated’ (in Stanza 147); (iv) manomayā: a tappurisa samāsa [Perniola, 1915/1997:165(c)], contraction of manas+mayā, with manas changing its final -as to -o; in many cases, however, the stem has passed to the thematic stem: āpas-maya > āpomaya ‘made of water‘ [ibid., p. 159(i)]

4manasā: (i) the singular instrumental case of mano; Geiger (2005, § 79, p.72.1) writes,” Not rare are the sg. instrumentals in –asā, formed on the analogy of as- stems on the basis of the equation mano:manasā = dhammo: x. Examples are found especially in the first two periods of the language, and again in the artificial poetry: they are rare in the post-canonical prose. Cf. balasā ‘with force’ (instead of balena) Th 1141; damasā beside damena Sn 655; padasā ‘on foot’ (instead of padena) Ja III 300.29 ….; hence, manasā= manena, instrumentative case of mana ‘mind;’ manasā is canonical, and manena is post-canonical.

From Duroiselle (1915/1997:41, No.159):

DECLENSION OF MANO, (STEM: MANAS) (masculine), THE MIND

singular plural

Nom. mano, manaṁ manā

Gen. manaso, manassa manānaṁ

Dat. manaso, manassa maninaṁ

Acc. mano, manaṁ mane

Ins. manasā, manena* manehi, manebhi**

Abl. manasā, manasmā, manehi, manebhi**

manamhā, manā

Loc. manasi, mane, manesu

manasmiṁ, manamhi

Voc. mano, manaṁ, manā, mana manā

Remarks:

(a) It should be borne in mind that mano is never used in the plural, although the forms are given by some grammarians.

(b) The influence of the a declension is here also clearly seen, principally in the plural, of which in fact, all the forms are after the a declension.

(c) There is also a neuter form in ni in the plural: manāni.

*manena: (a) manena is the post-canonical instrumentative case of mano (stem manas); the canonical form is manasā (Geiger, idem.); (b) euphonic combination or union, or sandhi,* of mano and the 3rd. pers. sg. masc. or neuter instrumentative suffix -ena ‘with, by’ with the elision or suppression sometimes of the final vowel in the first word (Tilbe, 1899:7, No.67), in this case mano, or of either the final vowel in the first word or the initial vowel of the second word, e.g., pana ime ‘but these’ > either paname or panime (Clough, 1824:9, No.18), or pana’me; tena+ime = tena’me (Duroiselle, 1915/1997:8, No. 21(b)); (c) when two different vowels come together, in this matter the final a in paduṭṭha and the initial e in -ena, usually the first, i.e., the final a, is elided and the second vowel, i.e., the initial e is lengthened if it happens to be in an open syllable: purisa ‘man’ + -ena > purisena ‘with a man;’ buddha-uppādo > buddhuppādo ‘the arising of a buddha;’ mano-indriyaṁ > manoindriyaṁ ‘the faculty of the mind.’

** (i) The forms in –bhi are mostly poetic (Tilbe, 1899: 10); (ii) The suffix –ebhi is mostly used in poetry and probably comes from the Vedic -ebhis [Duroiselle, 1915/1997:27(f), No.122], or archaic (Geiger, 1916/2005:73).

5.1 ce: (a) meaning if, a conditional conjunction, like the copulative conjunctions atha ‘and, then, now, else’ and atho ‘and, also, then,’ and the disjunction vā ‘or’ can never begin a sentence (Duroiselle, 1915/1997:129, No. 538), and, hence, they are called as enclitics. That’s why we can’t write or say “ce manasā paduṭṭhena ….”

In Pali, an enclitic, or just clitic, is a short word that always follows the other word to which it relates, and, hence, an enclitic can’t begin a sentence or statement. Enclitics form part of the nipāta or adverbs, which (according to Duroiselle, idem., p. 9, No.25) belong to the first type of indeclinable words: atho, atha, yeva, adho, yathā, tathā, tāva, yāva, eva, ivā, va, re, are, ca, hi, tu, kacci, kho, khalu, kira, pana, ce, nanu, nūna, nāma, etc.. The second type constitutes all the 20 prepositions: ā, u, ati, pati, pa, pari, ava, parā, adhi, abhi, anu, upa, apa, api, saṁ, vi, ni., nī, su, du, (saddanīti: catupadavibhāga).

5.2tato: (i) (sg. ablt.) therefrom, derived from Skt tatas; Geiger [2005, §66, p.58(a)] writes that final -as and -ar become -o: tato ‘therefrom’ = Skt tatas; pāto ‘early in the morning’ = Skt prātar. Both the forms puno and puna ‘again’ = Skt punar are found to occur. In verbal inflection, there often appears -a for Skt -as (§§ 157, 158.II) ….; (ii) tato (abl. sg. of pron. base ta (it), but used here as an indec.adv.) = thereupon, thereafter, hence, then (Sarao, 2009:2); (iii) the suffixes to, tra, tha, dha, ha, ham, and him form the adverbs of place. Before a short vowel, the t of tha is doubled: … (i) ta+-to= tato ‘thence, from that place;’ (ii) i (307.a) > iha, or idha ‘here in this place;’ (iii) i > ito ‘hence, from this place;’ (iv) eta (298,302) > etto, through etato (343) ‘hence’ (Duroiselle, 1915/1997:78-79, No.346).

5.1 & 5.2 There are two conjunctions: ce ‘if’ and tato ‘from that, by doing so;’ according to modern English and Indonesian grammars, only the first, ce, should be used. However, double consonants are common in social English and Indonesian.

6paduṭṭhena: (a) euphonic combination or union, or sandhi,* of paduṭṭha and the 3rd. pers. sg. masc. or neuter instrumentative suffix -ena ‘with, by’ with the elision or suppression sometimes of the final vowel in the first word (Tilbe, 1899:7, No.67), in this case paduṭṭha, or of either the final vowel in the first word or the initial vowel of the second word, e.g., pana ime ‘but these’ > either paname or panime (Clough, 1824:9, No.18), or pana’me; tena+ime = tena’me (Duroiselle, 1915/1997:8, No. 21(b)); (b) when two different vowels come together, in this matter the final a in paduṭṭha and the initial e in -ena, usually the first, i.e., the final a, is elided and the second vowel, i.e., the initial e is lengthened if it happens to be in an open syllable: purisa ‘man’ + -ena > purisena ‘with a man;’ buddha-uppādo > buddhuppādo ‘the arising of a buddha;’ mano-indriyaṁ > manoindriyaṁ ‘the faculty of the mind.’

*euphonic combination or union, or sandhi: Perniola (1997:7) writes that in the formation of a word, when two vowels come together, they are generally not allowed to remain (unchanged), but: 1) they are contracted into one, or b) one of them is elided, or c) a sonant vowel (i, ī, u, ū) is changed into its corresponding semivowel (y or v, as the case may be), or d) a consonant is inserted between them.

6.1bhāsatī: bhāsati (3rd pers.sg. pres. indic. act. of √bhās ‘to speak’’ = speaks; bhāsatī is m.c. for bhāsati, as a short vowel found before a single consonant, e.g., the vowel i before the single semi-consonant v in vā may be lengthened: (i) evaṁ gāme muni care = evaṁ gāme munī care; (ii) du+rakkhaṁ = dūrakkhaṁ; (iii) su+rakkhaṁ = sūrakkhaṁ (Duroiselle, 1906/1997:13, No. 32).

6.2 vā: (a) a coordinative conjunction; (b) a long vowel, like ā in vā, may be shortened to a, if it is followed by a single consonant, so that … vā karoti vā … should be rewritten into va karoti vā …; two other examples are given by Duroiselle (idem., No. 31): (i) yathā+bhāvi+guņena= yathabhāviguņena; (ii) yițțhaṁ vā hutaṁ vā loke= yițțhaṁ va hutaṁ va loke; (c) the second vā should retain its a, as the phrase to which it belongs forms a line in the present stanza: bhāsati vā karoti vā; however, the editorial team of the Dhammapada have retained both ā on account of the metre of this line. Otherwise, bhāsati should be rewitten as bhāsatī.

7naṁ:(i) a common substitute of taṁ, a neuter personal pronoun and also a demonstrative personal pronoun [Duroiselle, 1915/1997:70, No.294 and (c)]; the (initial) letter n generally substitutes for the initial t in any case of the three personal pronouns (or genders) so, sā, and taṁ where t occurs, and the middle t of any case of the three demonstrative pronouns eso, esā, and etaṁ where t occurs, e.g., tassa, tassā, taṁ, etassa, etassā, etaṁ, (ibid., No. 295):

| masculine |

feminine |

neuter |

| nassa = tassa |

nāya = tāya |

naṁ = taṁ |

| nena = tena |

nassā = tassā |

nena = tena |

| naṁ = taṁ |

nassāya = tassāya |

naṁ = taṁ |

| nasmā = tasmā |

nassaṁ = tassaṁ |

nasmā = tasmā |

| nasmiṁ = tasmiṁ |

nāyaṁ = tāyaṁ |

nasmiṁ = tasmiṁ |

| ne = te |

nā = tā, tāyo |

ne = te |

| nehi = tehi |

nāhi = tāhi |

nehi = tehi |

| nesaṁ = tesaṁ |

nāsaṁ = tāsaṁ |

nesaṁ = tesaṁ |

| nesu = tesu |

nāsu = tāsu |

nesu = tesu |

Duroiselle (ibid., No. 296) also writes that the forms with n above given are generally used when a noun has been already mentioned.

In the present and second stanzas of the Dhammapada, naṁ refers to bhāsati ‘one who speaks’ or karoti ‘one who acts.’

Duroiselle (ibid., No. 301) further writes that eso, esā, and etaṁ may sometimes be translated into that.

(i) (niggahīta), found always at the end of words, is, in Burma, pronounced like the m in jam, or ram; in Ceylon, it is pronounced like the ng in sing, or king (ibid., p.6)

8dukkhamanveti: (i) a euphonic union, or sandhi, of dukkha8.1 (nt.) ‘suffering;’ dukkhaṁ8.2 (sg. nom.) ‘suffering’ and anveti, 3rd person sg. act. indic., derived from anu- (pf.) ‘along, following, to’ + eti8.3 ‘goes’ = follows

8.1(a) dukkha, in this context, means suffering, or physical or mental pain, misfortune, unsatisfactoriness, evil consequence etc, and rebirth in the lower planes of existence, or in the lower strata of human society if born in the human world [Tin, 1956:1(3)];

(b) dukkha, cakka, sukha, rūpa and other nouns ending in a and their nominative case in ṁ are neuters.

Their declensions (following Duroiselle, 1915/1997:28, No.124)

106. DECLENSION OF RŪPA (NEUTER), FORM

singular plural

Nom. dukkhaṁ dukkhāni, dukkhā

Gen. dukkhassa dukkhānaṁ

Dat. dukkhassa, dukkhāya dukkhānaṁ

Acc. dukkhaṁ dukkhāni, dukkhe

Ins. dukkhena* dukkhehi, dukkhebhi**

Abl. dukkhā dukkhehi, dukkhebhi**

dukkhasmā

dukkhamhā, dukkhato

Loc. dukkhe, dukkhasmiṁ dukkhesu

dukkhamhi

Voc. dukkha dukkhāni, dukkhā

Remarks:

(a) ni is essentially the distinctive sign of neuter nouns in the nom. acc., and voc. plur. in all declensions.

(b) The final vowel of the stem is lengthened before ni.

*dukkhena: derived from dukkha + -ina in which the final a in dukkha and the initial i in -ina combine to produce e [ibid, p. 8, No.21, & p.27, No. 122(i) & Tilbe, 1899:10]

** (i) The forms in –bhi are mostly poetic (Tilbe, 1899: 10); (ii) The suffix –ebhi is mostly used in poetry and probably comes from the Vedic -ebhis [Duroiselle, 1915/1997:27(f), No.122], or archaic (Geiger, 1916/2005:73).

Other examples of neuter nouns (Duroiselle, 1915/1997:28, No. 124):

citta, mind sotta, ear

mūla, root, price veḷuriya, coral

upaṭṭhāna, service ahata, cloth (new)

jala, water osāna, end

loṇa, salt savana ,hearing

vajira, diamond sāṭaka, garment

vāta, wind pesana, despatch, sending

yotta, rope paṭṭana, a seaport

yuddha, fight paṇṇa, leaf

Remarks:

(a) It will be noticed that neuter nouns in a differ from the masculine in a, in the nom. and in the nom., acc. and voc. plur.; all the other cases are identical.

(b) In the plur. the nom. acc. and voc. have the same form.

(c) The form in āni, of the nom., acc. and voc. plur. is the most common.

8.2(a) niggahīta (ṁ) becomes m when it precedes a vowel (Duroiselle, 1915/1997, No.42): (i) taṁ+atthaṁ= tam atthaṁ; (ii) yaṁ+ahu= yam ahu; (iii) kiṁ etaṁ= kim etaṁ.

Duroiselle (ibid.) remarks:

Rules 39 and 42 are not strictly adhered to in texts edited in Roman characters; in proses above all, niggahīta is allowed to remain unchanged before a vowel or consonant, even in the middle of a vowel sometimes; in poetry, the retention of niggahīta or its change to m before a vowel is regulated by the exigencies of the meteres.

Duroiselle (ibid., No. 43) also writes:” Sometimes niggahīta before a vowel may become d: (i) etaṁ+attho= atadattho; (ii) etaṁ+eva+ etadeva; (iii) etaṁ+avoca= etadavoca; (iv) yaṁ+anantaraṁ= yadannantaram; (v) yaṁ+idam= yadidam

Duroiselle (ibid, Nos. 44-46) further writes:” Niggahīta before a vowel or consonant may be elided; niggahīta may sometimes be inserted before a vowel or consonant; a vowel may be elided after niggahīta.”

(b) Tilbe (1899:10-11) writes that when niggahīta (ṁ) meets either a vowel or consonant, the group may remain intact; niggahīta may be elided; a vowel following niggahīta may be elided; or one of the following changes may occur (with the examples in the parentheses given by the present author):

(1) niggahīta preceding a vowel generally changes to m;.a.1 or if the vowel is e, the group changes to ññ;a4(ii)

(2) niggahīta followed by a mute [mute sonants: (i) gutturals: g, gh; (ii) palatals: j, jh; (iii) linguals (or retroflex): ḍ, ḍh; (iv) dentals: d, dh, (v) labials: b, bh; (vi) liquids: y, r, ļ, v; (vii) aspirant: h)] is generally changed to the nasal (ń, ñ, ṇ, n, or m) of the class (guttural: ń, palatal: ñ, lingual (or retroflex): ṇ, dental: n; or labial: m) to which the mute belongs;a

(3) when niggahīta is followed by y, the group may become ññ;b or

(4) when niggahīta precedes h, it may change to ñ.a.3(iii)

asaṁ- or saṃ, an indeclinable prefix to verbal roots:* (1) implying a conjunction, e.g., with, together;’ (2) denoting (i) ’completeness,’ (opposite vi-):

(a)Duroiselle (1915/1997:14, No. 38) writes that the niggahīta when followed by a consonant may remain unchanged.

Examples:

(i) taṁ dhammaṁ kataṁ; (ii) taṁ khaņaṁ; (iii) taṁ patto

(b) Nasal-nasal: a nasal consonant (ń, ñ, ņ, n, or m) followed by another nasal consonant, is assimilated to the latter: saṁ-nisīdati > sannisīdati ‘he sinks down’ (Perniola, 2001:23, No.15(a);

a.1sam– before a vowel, e.g., samativijjhati derived from sam+ativijjhati;

a.2saṁ– before (i) a surd (or sibilant) (s), labial (b, bh, m, p, or ph), or glide (or semi-vowel) (y,* or v):, e.g., saṁsara, Saṁbuddha,* saṁyojana,b saṁyutta;b

* Saṁbuddha: (a) sam- + buddha, or buddha, derived from budh ‘to enlighten’ + -ta (a past participle suffix ; if formed from a transitive verb, it makes a passive meaning ; otherwise, it forms an active meaning) = budhta > buddha ‘enlightened.’ This is as written by Perniola [1997:17, No.13(a)] that when two mute consonants come together, the first is assimilated to the second since both are of the same strength:

yuj-ta > yutta ‘joined’

mad-ta > matta ‘intoxicated’

tadkāro > takkāro ‘he who does that’

sat-puriso > sappuriso ‘good man.’

The consonant t, however, preceded by one of the soft aspirate consonants gh, dh, or bh, is first shortened to d and then assimilation takes place:

labh-tum > labh-dum > laddhum ‘to bobtain’

lubh-ta > lubhda > luddha ‘greedy’

budh-ta > budh-da > buddha ‘enlightened ;’

(b) Duroiselle (ibid.,p 18, No.63) writes that when initial t follows a sonant aspirate (gh, jh, ḍh, dh, or bh), the assimilation is progressive: the final sonant aspirate loses its aspiration, the following t (surd) becomes sonant, viz. d, and, taking the aspiration which the final sonant has lost, becomes dh:

EXAMPLE:

√rudh+ta=rudh+da=rud+dha=ruddha

Remark: In the case of final bh, initial t having become dh, regressive assimilation takes place: √labh + ta = labh + da = lab + dha = laddha ‘(having) taken, obtained, received;’ (labhati ‘obtains, takes, receives’)

a.2.1 by assimilation, also san– before a dental (d, dh, t, th, or n), e.g., santapeti, sandahati;

a.3saṅ– or saṇ before a guttural (or velar) (k, kh, g, gh, and ṅ) or aspirate (h), e.g., (i)saṅgha ‘assembly, community, brotherhood, sisterhood, order, or a chapter of a certain Buddhist order, or a certain number of monks;’ (ii) saṅkhāra, saṅkhata, asaṅkheyya, saṇṭhana ‘configuration, position;’ (iii) saṇha ‘smooth, gentle, mild,’ (Andersen, 1907/1996:253); saṇheti ‘to brush down’ (Davids, 1921-1925/2005, Part VI, p.131);’ (iv) saṁ+ṭhițțhati > saṇṭhițțhati ‘stands;’ saṁ+ṭhānaṁ > saṇṭhānaṁ ‘position’ (called as assimilation or adaptation by Perniola, 1997:14, No. 11(b)]

a.4sañ- (i) before a palatal (c, ch, j, jh, or ñ), e.g., sañcarati [also found in Perniola, 1997:14, No.11(b)], sañchidati ‘to cut, ‘to destroy,’ sañjāti ‘birth, origin, outcome;’ sañjagghati ‘to joke,’ sañña ‘perception,’ viññū ‘intelligent, wise, learned, knowledgable;’ (ii) before a word beginning with e and the ñ, the initial e changes into ññ: taṁ+eva= taññeva, paccantaraṁ+eva= paccantaraññeva; (iii) before a word beginning with h: evaṁ hi kho= evañhi kho, taṁ+hitassa= tañhitassa (Duroiselle,1915/1997:14, No.40) [see also a.3(iii)];

a.5(i)sal- before the liquids l, ļ or ļh, e.g., sallakhetti ‘to observe,’ sallapati ‘to talk with;’ sa-before the liquid r, sometimes sā-, e.g., sāratta, sārambha (Davids, 1921-1925/2005, Part IV:114, Geiger, 2005, Section 74.3, & the present author’s own research);

(ii) Before initial l, the niggahita of saṁ and puṁ is changed to l:

(i) saṁ+lakkhaṇā=sallakkhaṇā; (ii) paṭi saṁ līno=paṭisallīno; (iii) saṁ+lekko=sallekho (Duroiselle, 1915/1997:14, No.39); (iv) puṁ+liṅgaṁ=pulliṅgaṁ (idem., No.39);

a.6 Duroiselle( idem., No.39) writes that the niggahīta, when followed by a consonant, may be transformed into the nasal of the class to which that consonant belongs.

EXAMPLES with (the explanatory notes in the parentheses being added by the present author):

(ix) raṇaṁ+jaho=ranañjaho (ñ belongs to the guttural (or velar) consonant class or group, consisting of g, gh, k, kh, and ń);

(x) taṇhaṁ+karo=taṇhańkaro;

(xi) saṁ+ṭhito=saṇṭhito (ṇ belongs to the cerebral or retroflex) consonant class or group, consisting of ț, th, ḍ, ḍh, and ṇ);

(xii) jutiṁ+dharo=jutindharo (n belongs to the dental consonant class or group, consisting of d, dh, t, th, and n);

(xiii) saṁ+mato=sammato (m belongs to the (bi-)labial consonant class or group, consisting of b, bh, p, ph, and m);

(xiv) evaṁ+kho=evań kho [see (i)];

(xv) dhammaṁ+ca=dhammañca (ñ belongs to the palatal consonant class or group, consisting of c, ch, j, jh, and ñ);

(xvi) taṁ+niccutaṁ=taññiccutaṁ;

bsaṁ- + yogo: the niggahīta following y is assimilated into the y, and both together may become ññ: saññogo

saṁ- + yuttaṁ: saññuttaṁ

Often, no coalescence takes place, and both letters remain unchanged:

saṁyuttaṁ, saṁyojanaṁ (Duroiselle, 1915/1997:14, No.41).

Examples taken by the present author from the other stanzas of the Dhammapada:

31: saṁyojanaṁ >saññojanaṁ

37: saṁyamessanti > saññamessanti

*(Davids, 1921-1925/2005, Part IV:114, Geiger, 2005, Section 74.3, & Tjan’s own research)

Davids (ibid.) writes that saṁ- (or saṃ–) is the second most frequently (16%) used prefix in Pali after vi- (19%).

8.3 (a) Duroiselle (ibid., No. 27.a.) also writes:” When u is followed by a dissimilar vowel, it is changed to v: (i) anu+eti*= anveti; (ii) dhātu+anta= dhātvanta; (iii) dhātu+attha= dhātvattha; (iv) bahu+ābādho= bahvābādho; (v) su+ agataṁ= svagataṁ; (f) anu+aḍḍhamasaṁ= anvaḍḍhamasaṁ;” (b) Another example (by the present author): su+akkhāta= svākkkhāta, with the lengthening of the initial a in akkhāta; but saṁ-anu-āgata > samannāgata ‘endowed with’ (c)Perniola [1997:23, No. 15(b)] writes about the sandhi of a final nasal consonant + an initial l, v, y, or r: nasal-l, v, y, r:

(i) n-u > av and sometimes an:

anu-eti > anveti ‘follows;’ anu-agā > anvagā ‘went after ;’ anu-aya > anvaya ‘conformity;’ duranu-aya > durannaya ‘difficult to find ;’ sam-anu-āgata > samaññāgata ‘endowed with’

(ii) n-y >ññ: man-yati > maññati ‘thinks ;’ akincan-ya > akiñcañña ‘nothingness’

(iii) m-y > mm, my, ñd :

āgam-ya > āgamma ‘having come’

saṁ-yogo > saṁyogo*/saññogo ‘bond’ (*Perniola spells it as saṃyogo, as he does all over his book) ;

(iv) Etc.

*eti: formed from √i ‘go’ + -ti [a personal suffix indicating the 3rd pers. sg. act. indic. case; Duroiselle (1917:145, No.578) writes that it also forms a numerous class of actions nouns, fem. agent-nouns, and a limited number of adjectives; fem.: √bhaj ‘to divide’ + -ti = bhatti [also bhakti, No. 426 remarks, 59(a)] ‘division;’ √kitti ‘to praise’ + -ti = kitti (with one t dropped) ‘praise; √gam ‘go’ + -ti = gati ‘ a going, journey.’ From √muc, mutti ‘deliverance; from √man ‘ to think,’ mati (455), thought, etc. Adj.: √ṭha ‘stand, last’ + -ti = ṭhiti ‘lasting; √pad ‘to go, step’ + -ti = patti (64) ‘going, a foot soldier.], so that eti means goes (Davids, Part I, p.61), with the the strengthening (or guṇa) of the root √i to e (Duroiselle, ibid., pp. 22-23, Nos. 101, 105-110);

From Tilbe, ibid., p.6

9 (i) vahato: It is an optional form of vahantassa, which is an ablative case and also a genitive case of a masculine noun or adjective ending in -a; the entire suffix -ntu and the inflection endings -sa, -smiṁ, and nā are changed to -to, -ti, and -tā, respectively. Examples: gunavantassa > gunavato ‘of/for one who has virtue; gunavantu+-smiṁ > gunavati ‘ in one who has virtue;’ gunavantu+ -nā > gunavatā ‘from/by/with one who has virtue’ (Kaccayana, § 127.102); (ii) It is curious that vahatu, an ox, is not found in PED or CPED (Anandajoti, www.ancient-buddhist-texts.net)

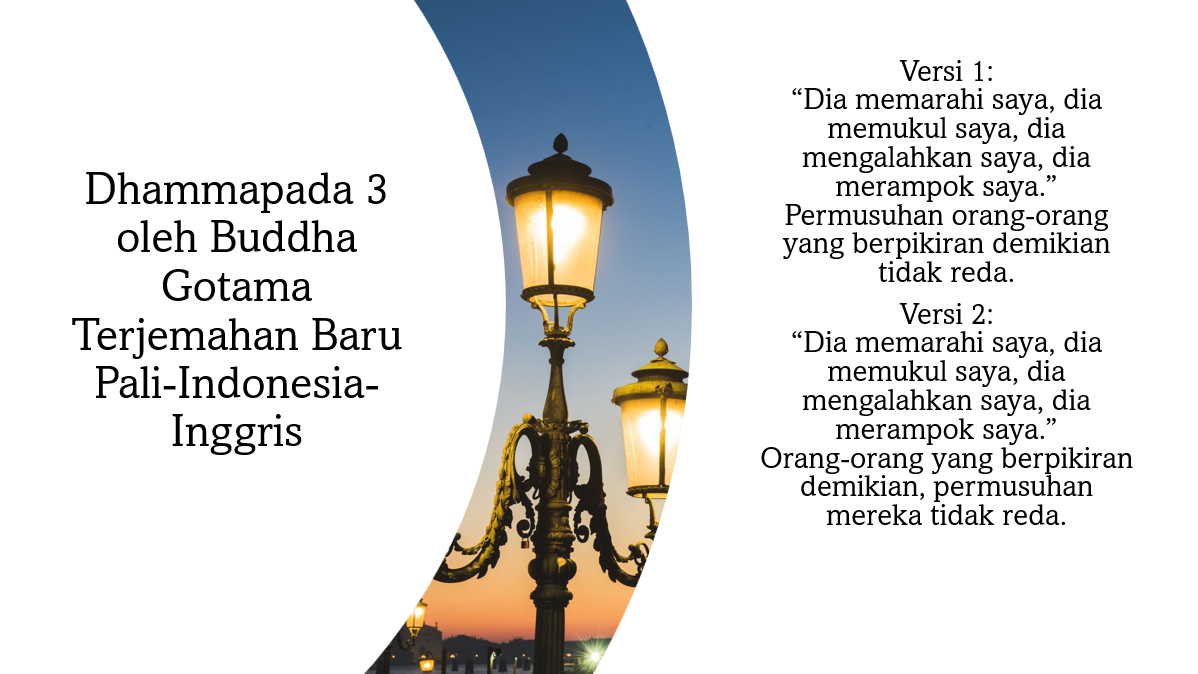

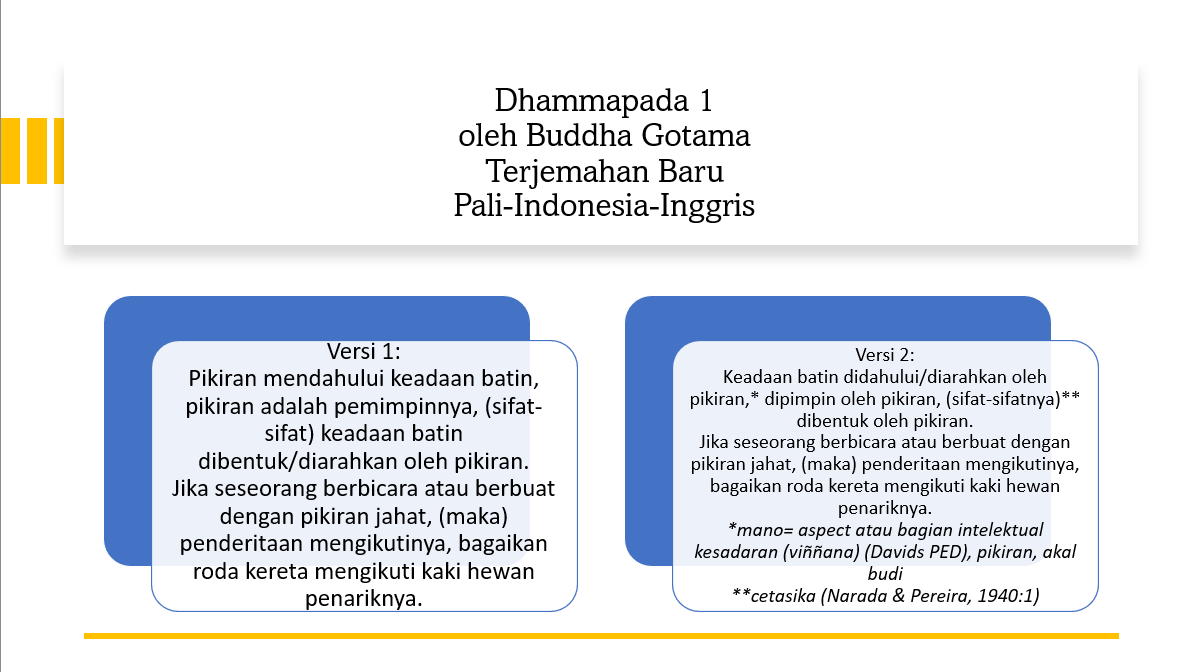

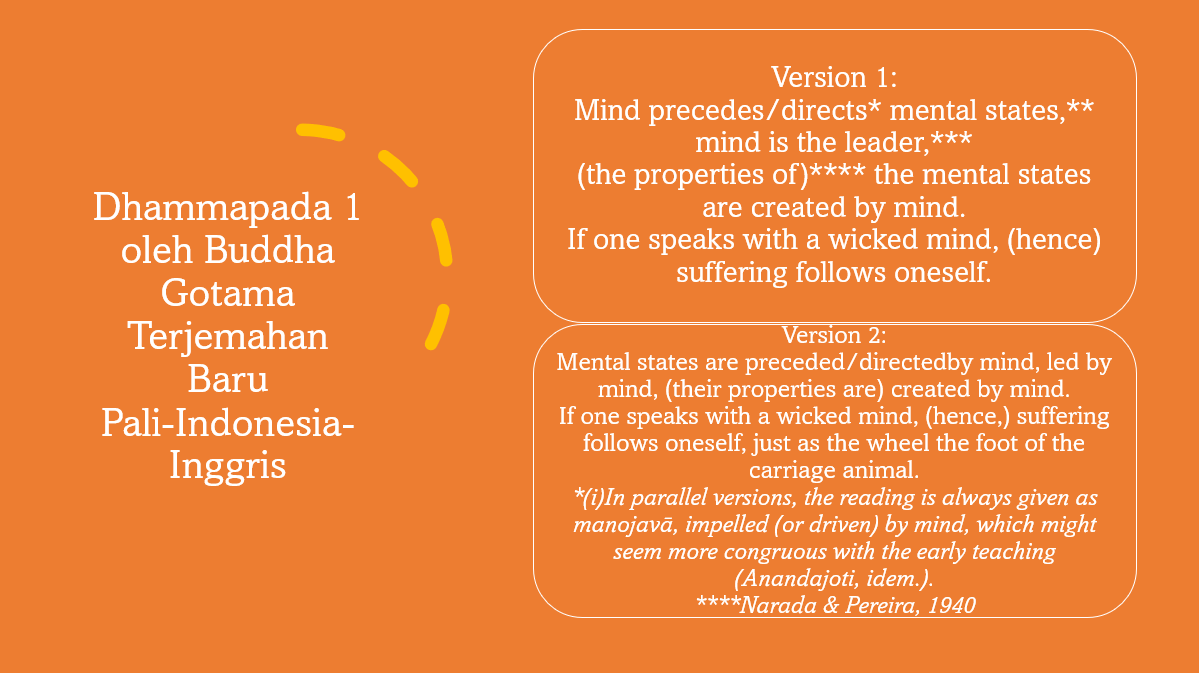

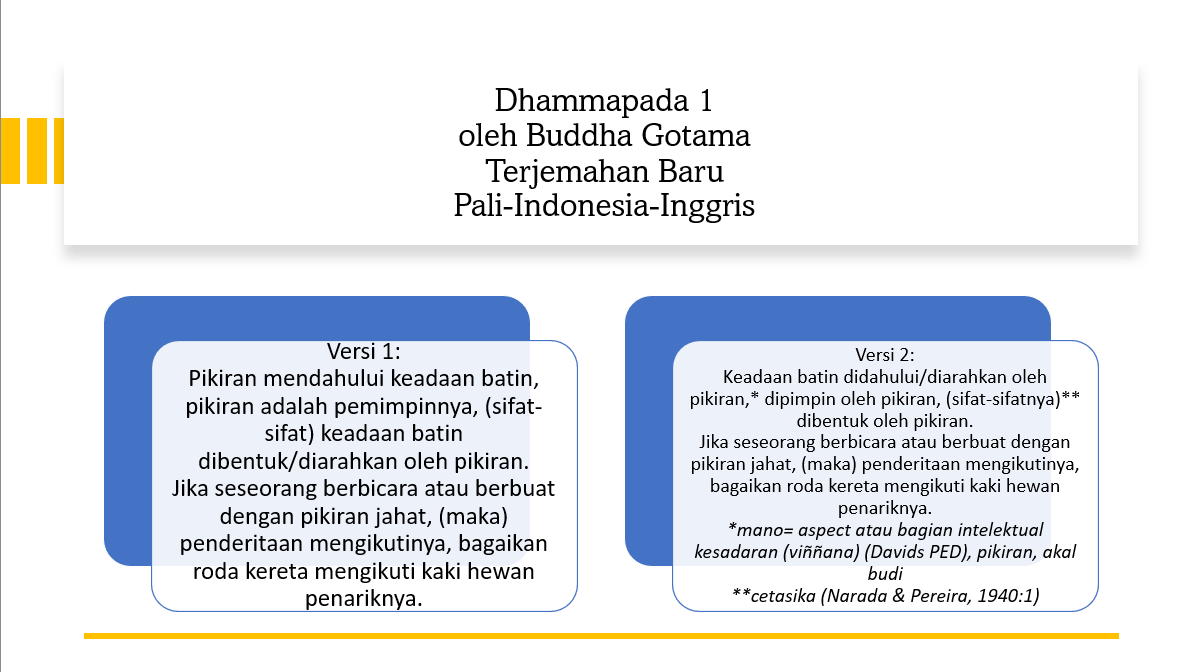

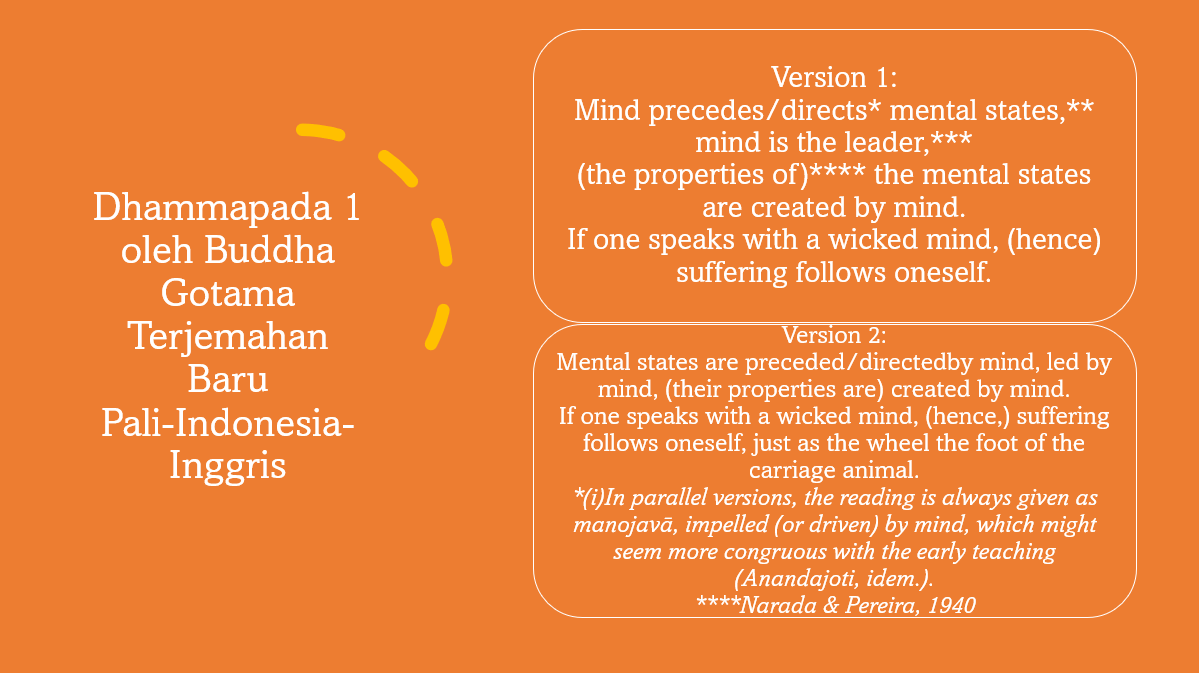

Perbandingan 2 terjemahan

English 1:

Anāndajoti |

English 2:

Burlingame |

Mind precedes thoughts, mind is their chief,

their quality is made by mind,

if with base mind one speaks or acts

through that suffering follows one

like a wheel follows ox’s foot. |

Thought is of all things first, thought is of all things foremost, of thought are all things made. If with thought corrupt a man speak or act. Suffering follows him, even as a wheel follows the hoof of the beast of burden. |

Indonesia 1:

BDG |

Indonesia 2:

CDD |

| Segala keadaan pikiran dipimpin oleh batin. Batin adalah pemuka dan pembentuknya. Apabila seseorang berucap atau bertindak dengan pikiran jahat, penderitaan niscaya akan mengikutinya ibarat roda pedati yang mengikuti jejak kaki lembu yang menariknya. |

Segala keadaan batin didahului oleh pikiran, dipimpin oleh pikiran, dan dibentuk oleh pikiran. Apabila seseorang berkata atau berbuat dengan pikiran jahat, oleh karena itu penderitaan akan mengikutinya seperti roda (pedati) yang mengikuti jejak (lembu) yang menariknya. |

Mari teman-teman pilih mana yang paling benar. Tulis komentar dibawah ini ya…